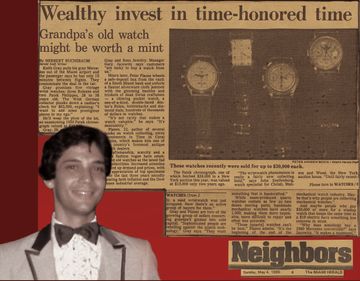

Wealthy invest in time-honored time Grandpa’s old watch might be worth a mint

Originally published in the Miami Herald Neighbors Section in 1986, we are proud to reintroduce an article featuring Gray & Sons founder Keith Gray—just 29 years old at the time—at the dawn of his enduring passion for Swiss timepieces, a journey that began over 45 years ago. This Time Capsule article proves that watch collectors have always shared the same passion and appreciation for the art of Swiss watchmaking—a tradition that continues to thrive at Gray & Sons today.

“Wealthy invest in time-honored time Grandpa’s old watch might be worth a mint"

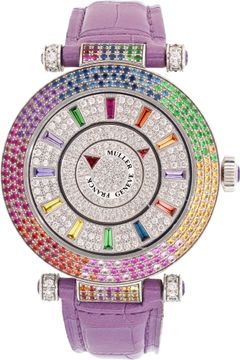

Keith Gray rolls his gray Mercedes out of the Miami airport and the passenger says he has only 15 minutes between flights. They consummate the deal in the car. Gray promises five vintage wrist watches; three Rolexes and two Patek Philippes, 28 to 38 years old. The West German collector plunks down a cashier’s check for $63,500, explaining: “I want to add some prestigious pieces to my ego.” He’ll wear the plum of the lot, an unassuming 1950 Patek chronograph valued at $30,000. Gray, 29, owns Coconut Grove’s Gray and Sons Jewelry. Manager Gary Jacowitz says customers “are lucky to buy a watch from us.”Hours later, Peter Planes wheels a safe-deposit box from the vault of a South Miami bank and unfurls a flannel silverware cloth jammed with the gleaming baubles and trinkets of dead Swiss craftsmen — a ticking pocket watch, a one-of-a-kind, double-faced doctor’s Rolex, bubblebacks and diamond dials, hundreds of thousands of dollars in watches. “It’s not rarity that makes a watch valuable,” he says. “It’s desirability.” Planes, 22, author of several books on watch collecting, owns Investment In Time of Coral Gables, which makes him one of the country’s foremost antique watch dealers.

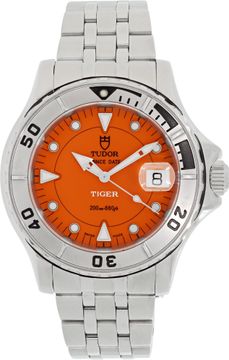

Craftsmanship, scarcity and a retro fashion vogue have established old watches as the latest fad in collectibles. Increased attention kicked up demand and prices, with the appreciation of hot specimens over the last three years soundly beating both inflation and the Dow Jones industrial average.

"The wristwatch phenomenon is really a fairly new collecting field,” says John Snellenburg, watch specialist for Christie, Manson and Woods, the New York auction house. “Until fairly recently, a used wristwatch was just scrapped. Now there’s an active group of buyers for them.” Gray and Planes are pro of the growing group of sellers converting grandpa’s gizmos into cold capital. “Sophisticated people are rebelling against the quartz technology,” Gray says. “They want something that is handcrafted.” While mass-produced quartz crystals contain as few as two dozen moving parts, handmade mechanical watches have nearly 1,000, making them more expensive, more difficult to repair and often less accurate.

“Those [quartz] watches can’t be beat,” Planes admits. “It’s the beginning of the end of the mechanical watch industry. Maybe that’s why people are collecting mechanical watches.” And maybe people who pay $30,000 or more for a windup watch that keeps the same time as a $10 electric have something less concrete in mind. “Why does somebody buy a 1960 Mercedes convertible?” says Jacowitz. “It makes a statement.”

A MIAMI JEWELRY STORE IS INVESTING IN THE FUTURE OF STUDENTS

NEXT ARTICLE

Pre-Owned Luxury Watches for January 2026: Your New Year's Resolution Guide to Self-Investment Excellence